Department of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Saudi

Electronic University, Riyadh 11673, Saudi Arabia

Corresponding author email: shaima.ali.miraj@gmail.com

Article Publishing History

Received: 01/02/2025

Accepted After Revision: 15/03/2025

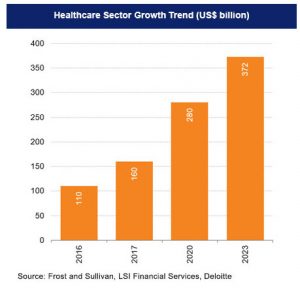

The Indian healthcare sector is growing at a brisk pace due to its strengthening coverage and services and increasing expenditure by public and private players. It has undergone significant transformations over the last 75 years, but still faces several challenges. The Indian healthcare market, which was valued at US$ 110 billion in 2016, is now projected to reach US$ 638 billion by 2025. It is noteworthy that much progress has been made in the country’s healthcare management since independence. Life expectancy is greater than 67 years, and the India of 2025 is a thriving democracy with a diversified production base, a large scientific community, and an impressive information technology sector. This review article discusses the past and present of the Indian healthcare system and its management concerning the problems and challenges it has faced over the last many decades.

Healthcare has become one of India’s largest sectors, both in terms of revenue and employment, as it comprises hospitals, medical devices, clinical trials, outsourcing, telemedicine, medical tourism, health insurance, and medical equipment. The Indian healthcare sector is growing at a brisk pace due to its strengthening coverage, services, and increasing expenditure by public as well as private players. India’s competitive advantage lies in its large pool of well-trained medical professionals. India is also cost-competitive compared to its peers in Asia and Western countries. Moreover, India has emerged as a hub for R&D activities for international players due to its relatively low cost of clinical research. The telemedicine market is also expected to reach US$ 6 billion by 2025, driven by increased demand for remote healthcare solutions and advancements in technology.

Public Health, Management in India, Past and the Present.

Miraj S. A. Public Health Care and its Management in India: Challenges and Opportunities from the Past and the Present. SSN Journal of Management & Technology Research Journal. 2025;2(1).

Miraj S. A. Public Health Care and its Management in India: Challenges and Opportunities from the Past and the Present. SSN Journal of Management & Technology Research Journal. SSN Journal of Management & Technology Research Journal. 2025;2(1). Available from: <a href=”https://surl.li/htfkqw“>https://surl.li/htfkqw</a>

INTRODUCTION:

Background of health and the health care system: Healthcare has become one of India’s largest sectors, both in terms of revenue and employment. It comprises hospitals, medical devices, clinical trials, outsourcing, telemedicine, medical tourism, health insurance, and medical equipment. The Indian healthcare sector is growing at a brisk pace due to its strengthening coverage and services and increasing expenditure by public and private players. It has undergone significant transformations over the years, but still faces several challenges.

India’s healthcare delivery system is categorized into two major components – public and private, offering medical services and infrastructure to the 1.4 billion people living in India. The government, i.e., the public healthcare system, comprises limited secondary and tertiary care institutions in key cities and focuses on providing basic healthcare facilities in the form of Primary Healthcare Centers (PHCs) in rural areas. The private sector provides the majority of secondary, tertiary, and quaternary care institutions with a major concentration in metros, tier-I, and tier-II cities. India’s competitive advantage lies in its large pool of well-trained medical professionals.

India is also cost-competitive compared to its peers in Asia and Western countries. The cost of surgery in India is about one-tenth of that in the US or Western Europe. The low cost of medical services has resulted in a rise in the country’s medical tourism, attracting patients from across the world. Moreover, India has emerged as a hub for R&D activities for international players due to its relatively low cost of clinical research.

Primary healthcare services are the individual’s first point of contact and are provided through primary health centers, community health centers, and sub-centers. Secondary care focuses on acute and specialist services provided by district hospitals. Tertiary care refers to advanced medical services, including specialty and super-specialty services provided by medical colleges. The private sector consists of individual practitioners, nursing homes, clinics, and corporate hospitals [1,2].

Health has been assumed as a gigantically growing industry, and the potential is tremendous as India’s spending on health is dismal, far below the 2017 National Health Policy average of 2.5 %. As a result, there has been a sudden rise in private hospitals and their successful blooming. Hospitals in major cities in India in many cases are run by business houses, using corporate business strategies and high-tech specializations, which create demand and attract high-profile patients as the facilities in some of these hospitals are world-class [3,4].

The Indian healthcare market, which was valued at US$ 110 billion in 2016, is now projected to reach US$ 638 billion by 2025. The healthcare sector, as of 2024, is one of India’s largest employers, employing a total of 7.5 million people [5]. India has supported the ideal of health for all since it became an independent nation more than 75 years ago. The Bhore Committee report in 1946 recommended a national health system for the delivery of comprehensive preventive and curative allopathic services through a rural-focused multilevel public system, financed by the government, through which all citizens would receive care irrespective of their ability to pay [6,7].

The health care system in India received a setback in its development over the last many years because of severe unavoidable circumstances, for example, the memories of the Bengal famine of 1943, which killed 2-3 million people are still haunting us, the fact that health services were concentrated in urban areas, and health indicators were universally poor with a life expectancy at birth of 37 years during the country’s bloody partition and independence in 1947, [7].

However, much progress has been made since then. Life expectancy is greater than 67 years, and the India of 2025 is a thriving democracy with a diversified production base, a large scientific community, and an impressive information technology sector. During the same period, however, India’s record in expanding social opportunities has been uneven. The health and nutritional status of children and women remains poor, and India is routinely ranked among countries performing weakly on overall health performance (8). But there is good reason for hope. The country has withstood the recent global economic crisis and quickly returned to economic growth.

Concerning India’s public health care system it is still pathetic. India has one of the most fragmented and commercialized healthcare systems in the world, where world-class care is greatly outweighed by unregulated, poor-quality health services for the general people. Because public spending on health has remained low, private out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures on health are still among the highest in the world [9].

Recent data show that there has been a considerable increase in government expenditure, decreasing the OOP from a high of 62.6% in 2014 to a low of 39,4%. Between 2014-15 and 2021-22, the government’s share of health expenditure grew from 1.13% to 1.84% of GDP, allowing for enhanced public healthcare facilities and services. This increase makes healthcare more accessible and affordable, reducing individuals’ need to pay out of pocket [10].

Health care, far from helping people rise out of poverty, has become an important cause of household impoverishment and debt. The average national health indicators, though showing improvements in recent decades, hide vast regional and social disparities. Although some privileged individuals enjoy excellent health outcomes, while others experience the worst imaginable conditions [11]. Health disparities are being exacerbated by unequal economic growth, growing commercialization of health care, and poor regulation of costs and quality of care [9]. As citizens of India, we have witnessed these injustices not professionally, but through our experiences of sickness in our families.

Healthcare paints a dire picture where India is short by a staggering 2.4 million hospital beds, leaving millions without access to proper medical treatment. India, which is meant to be utilizing its demographic advantage, seems to be overlooking its most valuable asset, people [12].

Healthcare in the new budget allocation has increased from Rs 33,150 crores in 2015 -16 to Rs 95,957 crores, a more than 100 percent jump. despite the increase, Indian hospital bed availability remains critically low, with just 1.4 beds per 1000 people, far below the WHO recommendation of 3.5 beds per 1,000. Between 2014-15 and 2021-22, the government’s share of health expenditure grew from 1.13% to 1.84% of the GDP, allowing for enhanced public healthcare facilities and services. This increase makes healthcare more accessible and affordable, reducing individuals’ need to pay out of pocket [10]. Worse, for 1000 people, government hospitals have an even more alarming ratio of 0.79 beds per 1000, meaning the country is short by 2.4 million beds. The doctor-to-patient ratio stands at 1:1,511, again failing to meet the WHO-recommended 1:1000.

Definition of Health: As per the definition, health does not simply refer to the absence of disease, but to a state of well-being, wholeness, harmony, equilibrium and quality or fullness of life, [13]. The healthcare system in India is characterized by multiple systems of medicine, mixed ownership patterns, and different kinds of delivery structures. However, it is the primary duty of the constituent states and the government to look after the well-being of every individual. The constitution charges every state with raising of the level of nutrition and the standard of living of its people and the improvement of public health as among its primary duties. The health financing system in India is dependent on government budgetary allocations and private funding. The role of private financing has increased significantly in recent years. It is estimated that people spend about 4.9 % of the GDP on healthcare needs and this is about three-fourths of the healthcare expenditure [14].

Most of the health care funding is out-of-pocket private expenditure which has grown at the rate of 12.5% and for each 1% increase in the per capita income it has increased by 1.44%. Thus in the absence of effective regulation of private health services, healthcare costs are inevitably high, and it is the poor people of lower income groups who suffer most, [15].

Healthcare System and Its Importance: The health system in India is under severe strain, and one of the management experts even writes that naming what exists in a health care system may not be accurate because it largely concerns the management and treatment of sickness and disease, not vibrant good health. Longevity has not been accompanied by good health. This has been criticized as adding years to life without adding life to years, [16].

The private healthcare system in India has grown vastly over the years and is well-established and flourishing. At the time of Independence, the private health sector accounted for only 5 to 10 percent of total patient care. In 2004, the share of the private sector in total hospitalized treatment was estimated at 58.3 percent in rural areas and 61.8 percent in urban areas. In Haryana, a majority of chest symptomatic (75 percent of the male patients and 75 percent of the urban patients) obtained care from the private sector, for outpatient care, 77 percent went to private sources in Kerala [17].

Slum dwellers in Indore sought outpatient care predominantly from the private sector [18]. In Dehradun, only 25 per cent of the elderly went to a government source for medical care [19].A study of six states reported that the proportion of people who went to private health facilities was high, varying between 63 and 83 per cent in three North Indian states, [20] . It is a pleasant surprise that, India has developed an extensive network of healthcare infrastructure since independence. The system envisages availability and accessibility of publicly funded healthcare to all, regardless of their ability to pay. However over a period of time due to expansion in size and a shortfall in budgetary support, burdened due to a huge population, the public health care system has lagged behind in terms of its ability to meet the challenge of fulfilling the health needs of a large segment of the rapidly growing population.

Role of Private Health Care System: To meet this challenge partially, the private health care sector has grown in size and scope. Consequently, the present health care system is characterized by having providers belonging to ownership of both public and private facilities and providers practicing in different systems of medicine. Both public and private facilities provide health services, but the bulk of the curative services are skewed towards the urban areas and dominated by the private sector in India. Private health expenditure is in nominal terms is growing very fast and with the proliferation of advanced medical technologies, new treatment protocols, equipment, the health care costs are increasing. To meet these increasing costs of treatment health insurance is highly justified. Though the need is quite high, the growth of health insurance is very slow, as compared to developed countries and even the developing countries. It is an established fact that, health care spending in India is very high, much more than the developing nations.

Though India is one of the fastest growing economies with an expected growth rate in 2025-26 to between 6.5 to 6.8, despite its high growth rate, its rank is 134 on the Human Development Index [21].

Total public expenditure on health in the country as a percentage of GDP now stands at less than 2 %, however, health-related expenditures like clean drinking water, sanitation, and nutrition have a major bearing on health and if expenditure on these is counted, the total public health spending reaches around 1.5 percent of GDP. Even so, it is strongly felt that public expenditure on health needs to be increased. On the other hand, the country is gripped with communicable and non-communicable diseases resulting from changing lifestyles, while on the other hand, healthcare costs are escalating making access to quality healthcare difficult.

History of Healthcare in India: Historically, the art of health care in India can be traced back nearly 3500 years. From the early days of Indian history, the Ayurvedic tradition of medicine has been practiced. During the rule of Emperor Ashoka Maurya 3rd Century BC, schools of learning in the healing arts were established. Many valuable herbs and medicinal combinations were discovered and created.

Even today many of these continue to be used. During his rein, there is evidence that Emperor Ashoka was the first leader in world history to attempt to give health care to all of his citizens, thus it was the India of antiquity which was the first state to give its citizens national health care. Modern medicine and health care were introduced in India during the colonial period. This was also a period that saw the gradual destruction of pre-capitalist modes of production in India. Under pre-capitalist mode of production institutionalised forms of health care delivery, as we understand them today, did not exist.

Practitioners who were not formally trained professionals but inheritors of a caste based occupational system provided health care within one’s village. This does not mean that there was no attempt at evolving a formal system. Charaka and Sushruta Samhitas, among other texts, is evidence of putting together a system of medicine. Universities like Takshashila, Nalanda and Kashi did provide formal training in Indian medicine. They were the Indian equivalent of Western alm-houses, monasteries and infirmaries which were provided with stocks of medicine and lodged the destitute, the crippled and the diseased who received every kind of help free and freely, [22,23,24,25,26,6,7].

Similarly, during the Mughal Sultanate, the rulers established such hospitals in large numbers in the cities of their kingdom, where all the facilities were provided to the patients free of charge. During the colonial period, hospitals and dispensaries were mostly state-owned or state-financed. The earliest literature available on medical practitioners is from the 1881 census, which records 108,751 male medical practitioners (female occupation data was not recorded!). Of these 12,620 were classified as physicians and surgeons (qualified doctors of modern medicine) and 60,678 as unqualified practitioners (which included Indian System Practitioners) [27].

The old concept of Piruvu (a collection) the forerunner of health insurance in India

Historically the concept of health insurance in India is not new, as social security for medical emergencies is not new to the Indian ethos. It is a common practice for villagers to take a ‘piruvu’ (a collection) to support a household with a sick patient. However, health insurance, as we know it today, was introduced only in 1912 when the first Insurance Act was passed followed by The Insurance Act of 1938, [28].

In Alma Ata (1978) (in old USSR), a global initiative towards health-related research and action was held in 1978. All the participants, including India, affirmed to ensure health for all by the year 2000, with primary health care as their top priority. But India perhaps understood it differently what Plato said “Attention to health is the greatest hindrance in life”. The Indian health insurance sector is still an immature baby, the victim of the ‘no common sense’ of the government.

The primary health care system in India is managed mainly by the shallow structure of government health-care facilities and other public- health care systems in a traditional model of health funding and provision. But, it is unable to justify the demand for health security for 300 million Indian health insurable population mainly due to service costs being out of the reach of many people, absence of good and effective number of physicians, low rate of education programs, less number of hospitals, poor medical equipment and over all, the poor budget of government towards the health program.

Therefore, the health insurance policies in India in the beginning years of independence were nothing less than a burden of inefficiency of a government-run system. Moreover, the uncontrolled and non-innovative attitude of the Indian bureaucracy always argued against the private players in the health insurance sector in India, which is still one of the problems in making insurance affordable for the middle-income group, which constitutes the majority of the most needy.

Health care was in a dismal condition before 1947, when the IA Act ushered in health insurance in India, [29], but we have made considerable progress in improving the health status of our country and health insurance is a significant emerging financial tool in meeting the health care needs of the people of India. Thus, a favorable demand, significant market potential, coupled with supportive infrastructure and the regulatory environment, started a boom in the Indian Health Insurance scene.

The current version of the Insurance Act was introduced in 1938. Since then there was little change till 1956 and 1972 when the Life Insurance industry and General Insurance Industry were nationalized and 107 private insurance companies were brought under the umbrella of the General Insurance Corporation (GIC). Private and foreign entrepreneurs were allowed to enter the market with the enactment of the Insurance Regulatory and Development Act (IRDA) in 1999, [30].

Development and growth of health insurance in Modern India: Seventy years before Indian population was grim. Memories of the Bengal famine of 1943, which killed 2—3 million people, have haunted us our health services were concentrated in urban areas, and health indicators were universally poor with a life expectancy at birth of 37 years [31]. Considerable progress has been made since then, particularly in the highly impressive information technology sector.

Since independence, the health care system in India has been expanded and modernized considerably, with dramatic improvements in life expectancy and the availability of modern health care facilities and better training of medical personnel. At the same time, however, much remains to be done. Most of the discussions on health care financing in India have centred on the financial constraints of the public sector and the efficiency of resource allocation by the government. ‘Health for all’ has been seen as the central assumption of the health sector debate, thus making the government the central player. While we admit that the ‘health system appears somewhat unrealistic – particularly in view of the fact that health spending in India is mostly private.

But still, poverty is the real context of India, as three-fourths of the population live below or at subsistence levels. The health and nutritional status of children and women remains poor, and India is routinely ranked among countries performing weakly on overall health performance. Recently, it has been reported that about 234 million people of India’s population are poor across 124 countries as measured by the Multidimensional Poverty Index [32]. The five countries with the largest number of people living in poverty are India, 234 million; Pakistan, 93 million; Ethiopia 86 million; Nigeria, 74 million; and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 66 million.

However, health-related expenditure like clean drinking water, sanitation, and nutrition has a major bearing on health and if expenditure on these is counted the total public health spending reaches around 2.5 percent of GDP, [33] .This means 70-90 per cent of their incomes go towards food and related consumption. In such a context social security support for health, education, housing etc. becomes critical. Ironically, India has one of the largest private health sectors in the world with over 80 per cent of ambulatory care being supported through out-of-pocket expenses, [34,35].

India has one of the most fragmented and commercialised health-care systems in the world, where world-class care is greatly outweighed by unregulated poor-quality health services. Because public spending on health has remained low, private out-of-pocket expenditures on health are among the highest in the world. Health care, far from helping people rise out of poverty, has become an important cause of household impoverishment and debt, [9].

Growth of Health expenditure in India in terms of GDP

Data showing expenditure on health in % of GDP from 1950 to 2025 based on a Report by Times Insight Group in association with J.P. Morgan.

| PERIOD | % GDP |

| 1950 -1951 | – 0.22 |

| 1960- 1961 | – 0.63 |

| 1970-1971 | – 0.74 |

| 1980-1981 | – 0.91 |

| 1990-1991 | – 0.96 |

| 2000-2001 | – 0.90 |

| 2009-2010 | – 1.09 |

| 2012 -2013 | – 1.2 % |

| 2024-2025 | 1.94% |

The average national health indicators, though showing improvements in recent decades, hide vast regional and social disparities. Although some privileged individuals enjoy excellent health outcomes, others experience the worst imaginable conditions, [36,11].

Health disparities are being exacerbated by unequal economic growth, growing commercialisation of health care, and poor regulation of costs and quality of care In India, despite improvements in access to health care, inequalities are related to socioeconomic status, geography, and gender, and are compounded by high out-of-pocket expenditures, with more than three-quarters of the increasing financial burden of health care being met by households. Health-care expenditures exacerbate poverty, with about 39 million additional people falling into poverty every year as a result of such expenditures, [36, 9 ].

Penetration of health insurance as an industry in India: The penetration of health insurance in India has been low. It is estimated that only about 3% to 5% of Indians are covered under any form of health

insurance. In terms of the market share, the size of the commercial insurance is barely 1% of the total health spending in the country. The Indian health insurance scenario is a mix of mandatory social health insurance (SHI), voluntary private health insurance and community-based health insurance (CBHI). Health insurance is thus really a minor player in the health ecosystem. Thus, with escalating health care costs coupled with demand for health care services and lack of easy access for people from the low income group to quality health care, health insurance is emerging as an alternative mechanism for financing health care [8,37].

Health insurance is complex, and there are serious market-failure problems. In any market-driven system, what should be produced, how it should be produced, and for whom it should ne produced are determined by market forces. Competitive environments take care that resources are used efficiently (at the lowest cost) and effectively (with optimum outcomes). Insurance protects against risks or uncertain events and is based on the principle that what is highly in unpredictable to an individual is predictable to a group of individuals. Health insurance protects against the cost of illness, mobilizes funds for health services, increases the efficiency of mobilization of funds and provision of health services, and achieves certain equity objectives.

Problems of health care management and health financing in India: According to various health reports in India, public health services are very inadequate. The public curative and hospital services are mostly in the cities where only 25 percent of more than one billion population reside. Rural areas have mostly preventive and promotive services like family planning and immunization. The private sector has a virtual monopoly over ambulatory curative services in both rural and urban areas and over half of hospital care, [13, 8,37].

According to the Planning Commission’s High Level Group headed by Dr. K.S Reddy who has recently said that India will take at least 17 more years before it can reach the WHO’s recommended norm of 1 allopathic doctor per 1000 people i.e by 2028 this important landmark in health care will be achieved, (38).Further, a very large proportion of private providers are not qualified to provide modern health care because they are either trained in other systems of medicine traditional Indian systems like Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha, and Homoeopathy, (AYUSH) or worse, do not have any.

The nation of India, with a population of 1.5 billion, experiences a vast inequity that exists in the healthcare industry, with barely 3 percent of the population covered by some form of health insurance, either social or private. The guiding principle of the Bhore Committee in 1946, that ‘no individual should fail to secure adequate medical care because of inability to pay for it’ looks unreachable still, after decades of Indian independence, [39].

Albert Einstein surely sleeps happily in the grave after seeing the Indian government’s practice of health management credo based on what he said fifty years back, “Common sense is the collection of prejudices acquired by the age of eighteen”. Unnecessary prejudice never allows our government to open the doors of health insurance to others. Indian(the government has never been sensible to understand that the opening of insurance sector in India will move individual health spending to collective spending backed by huge capital inflows into the health industry.

Future Perspectives: Healthcare has become one of India’s largest sectors, both in terms of revenue and employment. Healthcare comprises hospitals, medical devices, clinical trials, outsourcing, telemedicine, medical tourism, health insurance, and medical equipment. The Indian healthcare sector is growing at a brisk pace due to its strengthening coverage, services, and increasing expenditure by public as well as private players.

India’s competitive advantage lies in its large pool of well-trained medical professionals. India is also cost-competitive compared to its peers in Asia and Western countries. The cost of surgery in India is about one-tenth of that in the US or Western Europe. The low cost of medical services has resulted in a rise in the country’s medical tourism, attracting patients from across the world. Moreover, India has emerged as a hub for R&D activities for international players due to its relatively low cost of clinical research.

The telemedicine market is expected to reach US$ 5.4 billion by 2025, driven by increased demand for remote healthcare solutions and advancements in technology. In 2024, the Indian government established 60 new medical colleges, increasing MBBS seats by 6.3% to 1,15,812. This expansion has raised the total number of medical colleges to 766, up from 387 in 2013-14. Postgraduate seats also grew by 5.92% to 73,111.

In FY24 (Till February 2024), premiums underwritten by health insurance companies grew to Rs. 2,63,082 crore (US$ 31.84 billion). The health segment has a 33.33% share in the total gross written premiums earned in the country. The health-tech sector is set for significant expansion, with hiring projected to rise markedly.

India’s healthcare sector is extremely diversified and is full of opportunities in every segment, which includes providers, payers, and medical technology. With the increase in competition, businesses are looking to explore the latest dynamics and trends that will have a positive impact on their business. The hospital industry in India is forecast to increase to Rs. 8.6 lakh crore (US$ 132.84 billion) by FY22 from Rs. 4 lakh crore (US$ 61.79 billion) in FY17 at a CAGR of 16–17%. (40).

India is a land full of opportunities for players in the medical devices industry. The country has also become one of the leading destinations for high-end diagnostic services with tremendous capital investment for advanced diagnostic facilities, thus catering to a greater proportion of the population. Besides, Indian medical service consumers have become more conscious towards their healthcare upkeep. Rising income levels, an ageing population, growing health awareness and a changing attitude towards preventive healthcare are expected to boost healthcare services demand in the future. Greater penetration of health insurance aided the rise in healthcare spending, a trend likely to intensify in the coming decade.

CONCLUSION

According to various health reports in India, public health services are still inadequate. The public curative and hospital services are mostly in the cities where only 25 per cent of the more than one billion population reside. Rural areas have mostly preventive and promotive services like family planning and immunization. The private sector now has a virtual monopoly over ambulatory curative services in both rural and urban areas and over half of hospital care, better healthcare needs to be managed in a better way. As India is a land full of opportunities, players in the medical devices industry will have a bright future provided there is transparency of implementation of health benefit schemes both of the government and private players, particularly the corporate houses. The country has also become one of the leading destinations for high-end diagnostic services with tremendous capital investment for advanced diagnostic facilities, thus catering to a greater proportion of the population. Besides, Indian medical service consumers have become more conscious of their healthcare upkeep. Rising income levels, an ageing population, growing health awareness and a changing attitude towards preventive healthcare are expected to boost healthcare service demands in the future. Greater penetration of affordable health insurance can aid the rise in healthcare spending, a trend likely to intensify in the coming decade.

Conflict of Interest: The author declares no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement: Data will be available from the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Funding: Nil.

REFERENCES

- Kumar A The Transformation of The Indian Healthcare System Cureus. 2023 May 16;15(5) :e39079. doi: 10.7759/cureus.39079

- Health System. Information May; 2023 ;https://www.statista.com/markets/412/topic/454/health-system/#overview 2023 3 [Google Scholar]

- Wilson H Justice and the Social Determinants of Health: An Overview. Dr James Wilson – 2009 – Public Health Ethics 2 (3):210-213.

- Health Information Systems Technological and Management Perspectives Third Edition 2020 SpringerIndia Brand Equity Foundation IBEF Jan 2025

- Borkar, G. (1961): Health In Independent India,Revised Edition, New Delhi: Ministry of Health.

- Rao KN The nation’s health: Publications Division New Delhi 1966

- WHO World Health Statistics (2012) WHO’s annual compilation of health-related data for its 194 Countries

- Kumar AKS, LC Chen, M. Chaudhary, S. Ganju, V. Mahajan, A. Sinha,

- Sen (2011) Financing health care for all : Challenges and Opportunities, The Lancet, Volume 377, Issue 9766, Pp 668-679.

- National Health Accounts (NHA) Estimates for India 2021-2022

- Paul VK, Sachdev HS, Mavalankar D Reproductive health, and child health and nutrition in India: meeting the challenge. The Lancet 201110.1016/S0140-6736(10)61492-4. published online Jan 2012.

- Mohan D Frontline The Hindu Feb 06 2025

- WHO World Health Organisation Report: Reducing risks, promoting healthy life, WHO, Geneva 2002

- Sengupta A. and S. Nundy The private health sector in India , British Medical Journal , 2005 331:1157-1158

- Bhat R, Mavalankar D, Singh P, & Singh N Major causes and challenges in Health Insurance. Working paper 2007 No 2010 – 02-01-IIM, Ahmedabad

- Vombatkere S.G. Health Association, Dec 2007,5-6.

- Levesque, J. F., S. Haddad, D. Narayana, and P. Fournier. Outpatient are Utilization in Urban Kerala, India. Health Policy and Planning 2006 21 (4): 289–301.

- Islam M., M. Montgomery, and S. Taneja Urban Health Care- seeking Behaviour: 2006 A Cases Study of Slums in India and the Phillipines. Bethesda, Maryland. The Partners for Health Reform Plus Project, Abt Associates Inc.

- Kaushik, U. Elderly Perceived Health Needs: Assessment Survey in the States of Himachal Pradesh & Uttarakhand. March. 2009 Help Age India, New Delhi.

- Rao, P.H. The Private Health Sector in India: A Framework for Improving the Quality of Care. ASCI Journal of Management 2012 41 (2): 14– 39.

- HDI Human Development Index (HDI) UNDP 2025

- Heber D.The useful plants of India in Medicine. (1873)

- Friedrich KRA. Studies in the medicine of Ancient India. 1907

- Siegerist Henry A History of Medicine, Vol I 1951 Oxford University Press, London.

- Bhatia M, Susan B Primary Health Care, Now and Forever? A Case Study of a Paradigm Change Intl J of Social Determinants and Health Services 2009 Volume 43, Issue 3

- Gokhale BV Swasth Hind 4 165 1961

- Census Census of India 1881, vol. 3, Govt of India Delhi.

- Bhat R, S Maheshwari, S Sahu (2005) Third Party administrators and health insurance in India : Perception of providers and policy holders, IIM, Ahmedabad.

- IA : The Insurance Act As amended by Insurance (amendment) 1938 Act, [4 of 1938]

- IRDA Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority Act, 1999 amendment of the Insurance Act, 1938, the Life Insurance Corporation Act, 1956 and the General Insurance Business (Nationalisation) Act, 1972, Republic of India

- Famine Enquiry Commission Report 1945

- MPI The Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (2024) UNDP

- Kansara K & G Pathania A study of factor affecting the demand for health insurance in Punjab, Journal of Management & Science, 2012 Vol. 2 No 4 Page No 1- 9

- World Development Report 2020 Trading for Development in the Age of Global Value Chain

- UNDP Human Development Report 2022: The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene

- Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV .Health care and equity in India. The Lancet 2012-10. 1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6.published online Jan 12.

- WHO The World Health Report 2010: Health Systems Financing: the Path to Universal Coverage

- HLG, Planning Commission Report, (2010-2013).

- Banerjee, D Indian Journal of Medicine Education. Evolution Of The Existing Health Services Systems Of India March 1976

- Healthcare sector growth trend (Source: Frost and Sullivan, LSI 2024 Financial Services, Deloitte, Aranca Research)