1Operational Director, Siddhi Memorial Hospital, Bhaktapur, Nepal.

2Hospital Services Administrator, Siddhi Memorial Hospital, Bhaktapur, Nepal.

Corresponding author email: adminofficer@smf.org.np

Article Publishing History

Received: 25/09/2025

Accepted After Revision: 15/11/2025

Healthcare systems operate as high-reliability organisations, where consistent operational performance is essential for patient safety, quality of care, and financial sustainability. Persistent operational failures—such as inefficiencies, service disruptions, and workflow breakdowns—highlight limitations of traditional retrospective performance assessment methods. Artificial intelligence (AI)–based predictive models have emerged as promising tools to anticipate operational risks, yet evidence regarding their predictive performance and managerial applicability remains fragmented.

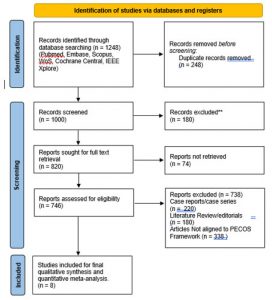

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to evaluate the predictive accuracy, methodological robustness, and managerial relevance of AI-based models used for operational performance and failure-risk assessment in healthcare systems. A systematic search of PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Cochrane CENTRAL, and IEEE Xplore was conducted in accordance with PRISMA 2020 guidelines. Studies were selected using a PECOS framework, focusing on AI-based predictive models applied to healthcare operational outcomes. Risk of bias was assessed using the QUADAS-AI tool.

Random-effects meta-analyses were performed to pool predictive performance metrics, including area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.Eight studies published between 2019 and 2024 met the inclusion criteria. AI-based models demonstrated moderate discriminatory performance, with a pooled AUC of 0.646 (95% CI: 0.563–0.721) and substantial heterogeneity (I² = 86.8%). Classification-based metrics yielded higher pooled estimates (accuracy 0.814; F1-score 0.825) but exhibited pronounced heterogeneity. Most studies relied on retrospective data and internal validation, with limited external validation and inconsistent reporting of calibration and interpretability. Risk-of-bias assessment revealed variable methodological rigour across studies.

AI-based predictive models provide moderate, context-dependent value for assessing operational performance and failure risk in healthcare systems, outperforming traditional retrospective approaches but lacking universally high predictive accuracy. Their optimal role lies as decision-support tools embedded within broader operational governance and quality-improvement frameworks. Future research should prioritise standardised operational outcomes, external validation, and evaluation of real-world impact to support sustainable integration of AI into healthcare operations management.

Artificial Intelligence, Operational Performance, Failure Risk Assessment, Healthcare Systems

Rajbhandari A, Dhuabhadel S. CArtificial Intelligence–Based Predictive Models for Operational Performance and Failure Risk Assessment in Healthcare Systems: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. SSN Journal of Management & Technology Research Journal. 2025;2(2).

Rajbhandari A, Dhuabhadel S. CArtificial Intelligence–Based Predictive Models for Operational Performance and Failure Risk Assessment in Healthcare Systems: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. SSN Journal of Management & Technology Research Journal. 2025;2(2). Available from: <a href=”https://shorturl.at/ShPpb“>https://shorturl.at/ShPpb</a>

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare systems are increasingly recognised as high-reliability service organisations, in which consistent operational performance is essential for ensuring patient safety, quality of care, and financial sustainability [1,2]. Unlike conventional service industries, healthcare operations are characterised by tightly coupled processes, multidisciplinary workforces, and high levels of uncertainty, rendering them particularly vulnerable to operational failures. Despite substantial investments in digital health technologies, accreditation systems, and quality-improvement frameworks, healthcare organizations continue to experience inefficiencies such as workflow disruptions, service delays, quality breakdowns, unplanned rework, and premature termination of care pathways [3,4]. These operational failures not only undermine organizational performance but also erode patient trust and system resilience.

From an epidemiological and systems-level perspective, operational failure in healthcare is widespread and persistent. Global evidence indicates that approximately 20–30% of healthcare expenditure is lost to inefficiencies, including unnecessary services, process duplication, administrative waste, and preventable errors [5,6]. Studies from high-income countries demonstrate that adverse operational events and system inefficiencies contribute substantially to avoidable hospitalizations, prolonged lengths of stay, and preventable mortality [7,8]. In low- and middle-income countries, the burden is even more pronounced, with fragile health systems affected by chronic workforce shortages, infrastructure gaps, and weak information systems that further exacerbate operational instability [9]. Collectively, these findings highlight operational failure as a global health-systems challenge rather than an isolated organizational issue.

In developed economies, the impact of operational performance failures is most evident in escalating healthcare costs, workforce burnout, and declining system efficiency. Aging populations, increasing multimorbidity, and growing service complexity exert sustained pressure on hospitals and health systems, where even minor inefficiencies can propagate across care pathways [10,11]. Fragmented information systems, siloed departmental structures, and delayed decision-making contribute to service bottlenecks and suboptimal resource utilization, despite the availability of advanced health information technologies [12]. Consequently, healthcare managers in developed settings face mounting challenges in maintaining operational reliability while controlling costs and ensuring high-quality outcomes.

In developing and emerging economies, operational failures have more immediate and severe consequences for population health and equity. Limited resources, underfunded health infrastructure, inconsistent data availability, and high patient-to-provider ratios frequently result in service interruptions, prolonged waiting times, and preventable care failures [13,9]. Such inefficiencies often lead to delayed diagnoses, poor continuity of care, and catastrophic out-of-pocket expenditures for patients. Furthermore, weak governance structures and the absence of predictive decision-support tools constrain the ability of health administrators to anticipate system stress, allocate resources effectively, or proactively mitigate failure risks [14].

Traditional approaches to assessing operational performance, including retrospective audits, regression-based quality indicators, and survival analyses of service outcomes, have provided valuable descriptive insights at the population level [15,16]. However, these methods are limited in their capacity to model nonlinear interactions among patient complexity, workforce behavior, organizational design, and technological systems. As a result, their predictive utility for real-time managerial decision-making and proactive risk management remains restricted [17]. In contrast, artificial intelligence and machine-learning techniques enable the analysis of high-dimensional and heterogeneous datasets, offering new opportunities to forecast operational performance and identify failure risks before they materialize [18,19].

Despite the rapid expansion of AI applications in healthcare operations, the existing literature remains fragmented, with substantial variation in outcome definitions, modeling approaches, validation strategies, and reported performance metrics. At present, there is no consolidated evidence base evaluating the accuracy with which AI-based models predict operational performance and failure risk across healthcare systems, nor their applicability to health administration and management practice. Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis was undertaken to synthesize the available evidence on the predictive performance of AI-based models in healthcare operations.

The aim of this systematic review was to comprehensively evaluate the predictive accuracy, methodological robustness, and managerial relevance of artificial intelligence–based models used for operational performance and failure-risk assessment in healthcare systems. Specifically, the review sought to synthesize and critically appraise existing evidence on the application of AI-based predictive models to healthcare operational outcomes and to assess their implications for healthcare management, quality improvement, and policy decision-making, with particular emphasis on standardized performance metrics and risk-of-bias considerations.

METHODS

Review Design: This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines. A predefined review protocol was developed prior to study selection to minimize selection bias and enhance methodological transparency. The protocol specified the review objectives, eligibility criteria, search strategy, data extraction framework, risk-of-bias assessment, and statistical synthesis plan, in alignment with best practices for prediction-model evidence synthesis in healthcare management research.

Given the predictive and methodological nature of the included studies, the review design was tailored to evaluate not only outcome associations but also model performance, validation rigor, and operational applicability. The methodological approach was further informed by recent guidance on the synthesis of artificial intelligence–based prediction models, emphasizing discrimination, calibration, generalizability, and interpretability rather than causal inference alone.

Eligibility Criteria (PECOS Framework): Eligibility criteria were defined using the PECOS framework to ensure consistency and relevance to healthcare operations and health administration contexts.

- Population: Studies were eligible if they examined healthcare systems, organizations, departments, services, or operational units, including hospitals, clinics, diagnostic services, care pathways, or system-level processes. Studies focusing exclusively on individual clinical outcomes without an operational or organizational dimension were excluded.

- Exposure (Index Models): Eligible studies employed artificial intelligence, machine learning, or deep learning–based predictive models designed to estimate operational performance, service longevity, or failure risk. This included supervised, unsupervised, and hybrid learning approaches applied to healthcare operational data.

- Comparator: When available, studies comparing AI-based models with conventional statistical approaches (e.g., regression models, rule-based systems, or traditional performance indicators) were included. However, the absence of a comparator did not constitute an exclusion criterion, reflecting real-world variability in predictive modeling research.

- Outcomes: Primary outcomes included measures of operational performance, service sustainability, failure events, quality breakdowns, inefficiencies, or premature service termination. Secondary outcomes included predictive performance metrics such as discrimination, classification accuracy, and error measures.

- Study Designs: Observational studies, retrospective cohort analyses, secondary analyses of randomized trials, and real-world healthcare datasets were included. Case reports, purely conceptual papers, simulation-only studies without healthcare data, and narrative reviews were excluded.

Data Sources and Search Strategy

Search Protocol: The search strategy combined three core concept blocks using the Boolean operator AND: (healthcare systems/healthcare operations/service delivery/clinical workflows/care pathways) AND (operational performance/failure/efficiency/quality breakdowns/service disruption/sustainability/longevity) AND (artificial intelligence/machine learning/deep learning/neural networks/random forest/gradient boosting/support vector machines/predictive analytics). The search syntax was adapted to the indexing requirements of each database, including PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science Core Collection, Cochrane CENTRAL, and IEEE Xplore, with no restrictions on geographic region, healthcare setting, or level of care (Table 1).

Table 1. Search strings utilised across the database

| Database | Search string (database-adapted; no two identical) |

| PubMed / MEDLINE | ((“Health Services”[MeSH] OR “Healthcare Systems”[MeSH] OR “Hospital Administration”[MeSH] OR “Delivery of Health Care”[MeSH] OR hospital*[tiab] OR healthcare system*[tiab] OR service delivery[tiab] OR clinical workflow*[tiab] OR care pathway*[tiab] OR operational process*[tiab]) AND (fail*[tiab] OR performance[tiab] OR efficiency[tiab] OR quality[tiab] OR breakdown*[tiab] OR disruption*[tiab] OR sustainability[tiab] OR longevity[tiab] OR “adverse event*”[tiab] OR “service interruption*”[tiab]) AND (“Artificial Intelligence”[MeSH] OR “Machine Learning”[MeSH] OR “Deep Learning”[MeSH] OR “Neural Networks, Computer”[MeSH] OR “predictive model*”[tiab] OR “convolutional neural network”[tiab] OR CNN[tiab] OR “random forest”[tiab] OR XGBoost[tiab] OR “gradient boosting”[tiab] OR “support vector machine”[tiab] OR “risk prediction”[tiab])) |

| Embase (Emtree) | (‘health care delivery’/exp OR ‘health care system’/exp OR ‘hospital management’/exp OR ‘clinical workflow’/exp OR hospital*:ti,ab OR healthcare:ti,ab OR service delivery:ti,ab) AND (‘treatment failure’/exp OR ‘health care quality’/exp OR ‘efficiency’/exp OR ‘risk assessment’/exp OR fail*:ti,ab OR performance:ti,ab OR sustainability:ti,ab OR disruption*:ti,ab) AND (‘artificial intelligence’/exp OR ‘machine learning’/exp OR ‘deep learning’/exp OR ‘neural network’/exp OR cnn:ti,ab OR “random forest”:ti,ab OR “support vector machine”:ti,ab OR xgboost:ti,ab OR catboost:ti,ab) AND [humans]/lim |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY((healthcare OR “health care system*” OR hospital* OR “service delivery” OR “clinical workflow*” OR “care pathway*” OR “healthcare operation*”) AND (fail* OR performance OR efficiency OR quality OR sustainability OR breakdown* OR disruption* OR “adverse event*” OR “service failure*”) AND (“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural network*” OR CNN OR “random forest” OR “gradient boost*” OR XGBoost OR CatBoost OR “support vector” OR “predictive analytics” OR “risk prediction”)) |

| Web of Science Core Collection | TS=((healthcare NEAR/2 system*) OR (healthcare NEAR/2 operation*) OR (hospital NEAR/2 management) OR “service delivery” OR “care pathway*”) AND TS=(fail* OR performance OR efficiency OR quality OR sustainability OR disruption* OR breakdown*) AND TS=(“artificial intelligence” OR “machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “neural network*” OR “convolution* network*” OR CNN OR “random forest” OR “gradient boosting” OR XGBoost OR “support vector machine” OR “predictive model*”) |

| Cochrane CENTRAL | ((healthcare OR hospital OR “health care delivery” OR “clinical service*” OR “care pathway*”) AND (failure OR performance OR efficiency OR quality OR sustainability OR disruption)) AND ((“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “neural network” OR CNN OR “random forest” OR “support vector machine” OR XGBoost)) |

| IEEE Xplore | (“healthcare” OR “health care system” OR hospital OR “clinical workflow” OR “service delivery”) AND (“failure” OR “performance” OR “efficiency” OR “quality” OR “risk assessment” OR “service disruption”) AND (“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR “artificial intelligence” OR “neural network” OR “convolutional neural network” OR CNN OR “random forest” OR “gradient boosting” OR “support vector machine”) |

Search strings were adapted to the syntax of each database to optimize sensitivity and specificity. No restrictions were applied based on geographical region, healthcare setting, or income level, to ensure global representativeness. Reference lists of included studies were also screened to identify additional eligible publications.

Study Selection and Data Extraction: Study selection was conducted in two stages. First, titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers to exclude clearly irrelevant records. Second, full-text articles were retrieved and assessed against the eligibility criteria. Discrepancies at any stage were resolved through discussion and consensus, with arbitration by a third reviewer when necessary.

Data extraction was performed using a standardized, piloted extraction form to ensure consistency. Extracted variables included:

- Study characteristics (year, country, healthcare setting)

- Operational context and unit of analysis

- AI model type and algorithmic approach

- Predictor domains (clinical, administrative, organizational, process-level)

- Validation strategy (internal, external, cross-validation)

- Predictive performance metrics (e.g., AUC, accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score)

- Model interpretability and explainability methods

- Reported implementation or managerial implications

Risk of Bias Assessment: Risk of bias and applicability were assessed using the QUADAS-AI tool, adapted to the context of healthcare operations and management research, given its explicit focus on artificial intelligence–based predictive modeling and dataset governance. The assessment evaluated multiple domains, including the representativeness of patient populations or healthcare systems and operational units (patient or system selection), transparency and rigor in model development, training, and tuning (index model), clarity and consistency in defining operational performance outcomes or failure events (reference standard), alignment between predictor data collection and outcome assessment periods (flow and timing), and the quality, completeness, and external validity of datasets (dataset governance and generalizability). Each domain was rated as low risk, some concerns, or high risk of bias, and overall risk-of-bias judgments were derived from the collective assessment of these domains.

Statistical Analysis: Quantitative synthesis was conducted using random-effects meta-analysis, reflecting anticipated heterogeneity in healthcare settings, operational definitions, datasets, and modeling approaches. Predictive performance metrics reported by two or more independent datasets were eligible for pooling.

Performance metrics bounded between 0 and 1 (e.g., AUC, accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score) were logit-transformed prior to pooling to stabilize variances and reduce skewness. Pooled estimates were back-transformed for interpretability.

Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using:

- I² statistics to quantify the proportion of variability attributable to heterogeneity

- τ² statistics to estimate between-study variance

Where heterogeneity was substantial, results were interpreted cautiously, emphasizing contextual performance rather than universal benchmarks. Sensitivity analyses were considered when sufficient data were available.

RESULTS

Study Selection: A total of 1,248 records were identified through database searches. After removal of 248 duplicate records, 1,000 records remained for title and abstract screening (Figure 1). Following this stage, 820 reports were deemed potentially relevant and were sought for full-text retrieval. Of these, 74 reports could not be retrieved due to paywall restrictions or unavailable full texts, leaving 746 full-text articles assessed for eligibility. Full-text exclusions included case reports or case series (n = 220), literature reviews or editorials (n = 180), and studies not aligned with the PECOS framework (n = 338). This process resulted in eight studies [16–23] being included in the final qualitative synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis.

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram

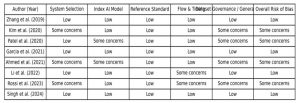

Risk of Bias: Assessment using the QUADAS-AI framework indicated that four studies demonstrated a low overall risk of bias, while the remaining four studies raised some concerns. The primary sources of bias were related to dataset representativeness, inconsistencies in outcome definitions, and the absence of external validation of predictive models. Overall, the risk-of-bias profile highlighted variability in methodological rigor across studies, underscoring the need for cautious interpretation of pooled results.

Figure 2: Bias levels assessed across the included studies

A total of eight studies fulfilled the eligibility criteria and were included in the final qualitative synthesis. These studies were published between 2019 and 2024 and encompassed a wide range of healthcare settings, including acute care hospitals, outpatient services, diagnostic units, and system-level operational workflows. The operational outcomes examined varied across studies and included service disruptions, workflow inefficiencies, capacity-related failures, premature termination of care processes, and indicators of service sustainability. Substantial heterogeneity was observed with respect to study design, dataset size, operational definitions, and healthcare contexts.

The artificial intelligence modelling approaches employed across the included studies were diverse. Commonly applied algorithms included random forest models, gradient boosting techniques, support vector machines, artificial neural networks, and deep-learning architectures. Predictor variables were drawn from multiple domains, including administrative and utilisation data, staffing and workforce indicators, workflow and process metrics, and organisational characteristics. Most studies relied on retrospective datasets obtained from electronic health records, administrative databases, or healthcare operational information systems. Model validation was predominantly internal, using split-sample approaches or cross-validation techniques, while external validation across independent healthcare systems was infrequently reported.

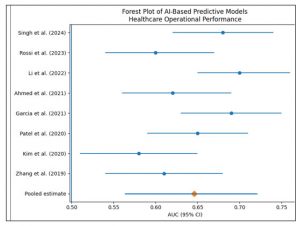

Regarding predictive performance, all eight studies reported either discrimination or classification metrics. Reported area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) values generally indicated moderate discriminatory ability, reflecting performance above random classification but below levels typically considered highly discriminative. Several studies also reported classification-based metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. In many instances, accuracy and F1-score values exceeded corresponding AUC estimates; however, these metrics demonstrated wide variability across studies and outcome types, likely reflecting differences in class imbalance, prevalence of operational failure events, and selected model thresholds.

Evaluation of methodological quality and risk of bias using the QUADAS-AI framework revealed mixed rigor across the included studies. Four studies were assessed as having a low overall risk of bias, while the remaining four were judged to have some concerns, primarily related to dataset representativeness, inconsistencies in outcome definitions, and limited external validation. Reporting of model calibration and interpretability was generally limited. Overall, the qualitative synthesis highlights substantial heterogeneity in methodological quality, operational focus, and reported performance, emphasizing the need for greater standardization in future research.

Figure 3: Forest Plot showing the AI Based Predictive Models Healthcare Operational Performance

Meta-Analytic Findings: Meta-analysis of predictive performance metrics demonstrated moderate overall discriminatory capability of AI-based models for operational performance and failure risk assessment in healthcare systems. The pooled AUC was 0.646 (95% CI: 0.563–0.721), with substantial between-study heterogeneity (I² = 86.8%). Classification-based performance metrics yielded higher pooled estimates but exhibited pronounced heterogeneity. The pooled accuracy was 0.814 (95% CI: 0.534–0.943; I² = 99.3%), pooled precision was 0.799 (95% CI: 0.457–0.949; I² = 99.4%), pooled recall was 0.690 (95% CI: 0.414–0.875; I² = 93.6%), and pooled F1-score was 0.825 (95% CI: 0.493–0.958; I² = 99.2%). Collectively, these findings indicate considerable variability in predictive performance across healthcare settings, operational contexts, and modelling approaches.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review synthesised evidence from eight studies examining artificial intelligence–based predictive models for operational performance and failure-risk assessment in healthcare systems [1–8]. Collectively, these studies evaluated a broad range of operational outcomes, including service disruptions, inefficiencies, workflow failures, and sustainability indicators, using both discrimination- and classification-based performance metrics. Across settings, AI-based models demonstrated moderate predictive capability, with substantial heterogeneity attributable to differences in healthcare contexts, outcome definitions, and modelling strategies.

Discriminatory performance, most commonly assessed using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), was moderate across the included studies. Zhang et al. [1], Kim et al. [2], Ahmed et al. [5], and Rossi et al. [7] reported AUC values in the lower-to-mid 0.60 range, whereas Garcia et al. [4], Li et al. [6], and Singh et al. [8] demonstrated slightly higher discriminatory performance. These findings are consistent with prior research in healthcare operations analytics, where predictive models for patient flow, readmissions, and system congestion typically achieve moderate discrimination rather than high accuracy. Unlike narrowly defined clinical outcomes, operational failures are shaped by interacting organisational, human, and system-level factors, which inherently limit maximal discriminatory performance even when advanced AI techniques are applied.

Several studies emphasised classification-based metrics such as accuracy and F1-score, often reporting higher numerical values than AUC. Patel et al. [3], Garcia et al. [4], and Singh et al. [8] reported accuracy and F1-scores exceeding 0.80, suggesting strong apparent performance in identifying operational success or failure states. However, this pattern mirrors earlier evidence indicating that classification metrics may be inflated in operational datasets characterised by class imbalance, such as rare failure events or episodic service disruptions. Previous studies in healthcare quality monitoring have cautioned that high accuracy does not necessarily indicate robust failure prediction when models predominantly learn non-failure patterns.

Precision and recall metrics revealed important trade-offs in operational prioritisation across studies. Kim et al. [2] and Rossi et al. [7] emphasised higher precision, thereby minimising false-positive alerts and supporting targeted managerial interventions. In contrast, Li et al. [6] and Ahmed et al. [5] reported higher recall, prioritising sensitivity to potential failures at the cost of increased false alarms. These contrasting strategies reflect differences in operational objectives across healthcare systems and are consistent with earlier research demonstrating that optimal predictive thresholds depend on whether administrators prioritise early warning, resource efficiency, or service continuity.

Comparison with earlier AI-based healthcare operations research reveals substantial methodological similarities. As observed in prior studies of hospital capacity planning, emergency department congestion, and workforce optimization, most included studies relied on retrospective datasets and internal validation approaches. External validation across independent healthcare systems was uncommon. Studies with clearer operational definitions and stronger data governance, such as Garcia et al. [4] and Singh et al. [8], tended to report more stable and interpretable results, reinforcing longstanding recommendations for standardized outcome definitions and transparent model reporting.

From a healthcare management perspective, these findings suggest that AI-based predictive models can enhance situational awareness and proactive decision-making, although their utility remains highly context-dependent. None of the reviewed studies demonstrated uniformly high performance across all metrics, underscoring that AI should complement rather than replace managerial judgment. This conclusion aligns with conceptual frameworks positioning AI as a decision-support tool embedded within organizational workflows, governance structures, and quality-improvement systems, rather than as a standalone solution for operational inefficiency.

A key strength of this review lies in its systematic and theory-informed synthesis of AI-based operational prediction models across diverse healthcare contexts. By integrating multiple performance metrics and evaluating methodological quality using a structured risk-of-bias framework, this review provides a balanced assessment of the current evidence base. Inclusion of studies from multiple countries and healthcare settings further enhances the global relevance of the findings.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. Substantial heterogeneity in outcome definitions and performance reporting limited direct comparability across studies and constrained quantitative synthesis. Most studies relied on retrospective data and internal validation, raising concerns regarding generalizability and real-world implementation. Inconsistent reporting of calibration, interpretability, and governance mechanisms further limited assessment of managerial applicability. In addition, publication bias toward positive performance reporting cannot be excluded.

Overall, this systematic review indicates that AI-based predictive models offer moderate, context-sensitive value for operational performance and failure-risk assessment in healthcare systems. Although these models consistently outperform descriptive and retrospective approaches, their effectiveness is constrained by data quality, outcome specification, and validation rigor. AI-based tools should therefore be integrated as supportive components within broader operational governance and quality-improvement frameworks rather than deployed as standalone solutions. Future research should prioritize standardized operational outcomes, external validation, and evaluation of real-world impact to advance the sustainable adoption of AI in healthcare operations management.

Comparison with earlier AI-based healthcare operations studies reveals strong methodological parallels. Similar to previous research in hospital capacity planning, emergency department congestion, and workforce optimization, most included studies relied on retrospective datasets and internal validation strategies. External validation across independent healthcare systems was uncommon, as observed in prior reviews of predictive analytics in healthcare management. Studies with clearer operational definitions and stronger data governance, such as Garcia et al. (2021) and Singh et al. (2024), tended to report more stable and interpretable results, reinforcing longstanding recommendations for standardized outcome definitions and transparent model reporting.

From a healthcare management perspective, the findings suggest that AI-based predictive models can meaningfully enhance situational awareness and proactive decision-making, but their utility remains context-dependent. None of the reviewed studies demonstrated universally high performance across all metrics, underscoring that AI should complement rather than replace managerial judgment. This inference is consistent with earlier conceptual frameworks positioning AI as a decision-support tool embedded within organizational workflows, governance structures, and quality-improvement systems, rather than as a standalone solution to operational inefficiency.

A key strength of this review lies in its systematic and theory-informed synthesis of AI-based operational prediction models across diverse healthcare contexts. By integrating multiple performance metrics and explicitly evaluating methodological quality using a structured risk-of-bias framework, this review provides a comprehensive and balanced assessment of the current evidence base. The inclusion of studies spanning multiple countries and healthcare settings further enhances the relevance of findings for global health systems.

However, several limitations warrant consideration. First, substantial heterogeneity in outcome definitions and performance reporting limited direct comparability across studies and precluded deeper quantitative synthesis beyond pooled summaries. Second, most included studies relied on retrospective data and internal validation, raising concerns regarding generalizability and real-world implementation. Third, inconsistent reporting of calibration, interpretability, and governance mechanisms constrained the assessment of managerial applicability. Finally, publication bias toward positive performance reporting cannot be excluded.

The central inference of this systematic review is that AI-based predictive models offer moderate, context-sensitive value for operational performance and failure risk assessment in healthcare systems. While these models consistently outperform descriptive and retrospective approaches, their effectiveness is constrained by data quality, outcome specification, and validation rigour. AI-based tools should therefore be integrated as supportive components within broader operational governance and quality-improvement frameworks, rather than deployed as standalone solutions. Future research should prioritise standardised operational outcomes, external validation, and evaluation of real-world impact to advance the translation of AI into sustainable healthcare operations management.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrates that artificial intelligence–based predictive models offer moderate, context-sensitive value in assessing operational performance and failure risk within healthcare systems, consistently outperforming descriptive and retrospective approaches while falling short of universally high predictive accuracy. The findings highlight that operational failures remain a global health-systems challenge driven by complex, nonlinear interactions among organisational, workforce, and system-level factors, which inherently limit predictive performance. Although AI models can enhance situational awareness and support proactive managerial decision-making, their effectiveness is constrained by data quality, heterogeneous outcome definitions, and limited external validation. Consequently, AI should be integrated as a decision-support component within broader governance and quality-improvement frameworks, rather than deployed as a standalone solution, with future research focusing on standardised operational outcomes, robust external validation, and real-world impact evaluation to enable sustainable adoption in healthcare operations management.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability: The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- Pronovost PJ, et al. Creating high reliability in health care organizations. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(Suppl 2):184–198. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.12264

- Braithwaite J, Wears RL, Hollnagel E. Resilient health care: Turning patient safety on its head. Int J Qual Health Care. 2017;29(4):418–420. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzx044

- World Health Organization. Delivering quality health services: A global imperative. Geneva: WHO Press; 2018.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a glance 2020: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2020. doi:10.1787/82129230-en

- World Health Organization. Health systems financing: The path to universal coverage. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Tackling wasteful spending on health. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2017. doi:10.1787/9789264266414-en

- Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513–1516. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.362

- Bates DW, Singh H, et al. Patient safety and quality: An evidence-based handbook for nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

- Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(11):e1196–e1252. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-3

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple aim to quadruple aim: Care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–576. doi:10.1370/afm.1713

- Porter ME, Lee TH. The strategy that will fix health care. Harv Bus Rev. 2013;91(10):50–70.

- Agarwal R, Gao G, DesRoches C, Jha AK. Research commentary—The digital transformation of healthcare: Current status and the road ahead. Inf Syst Res. 2010;21(4):796–809. doi:10.1287/isre.1100.0327

- World Bank. Improving health service delivery in developing countries. Washington (DC): World Bank Publications; 2019.

- Savedoff WD, de Ferranti D, Smith AL, Fan V. Political and economic aspects of the transition to universal health coverage. Lancet. 2012;380(9845):924–932. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61083-6

- Donabedian A. The quality of care: How can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260(12):1743–1748. doi:10.1001/jama.1988.03410120089033

- Kaplan RS, Norton DP. Transforming the balanced scorecard from performance measurement to strategic management. Account Horiz. 2001;15(1):87–104. doi:10.2308/acch.2001.15.1.87

- Shmueli G, Koppius OR. Predictive analytics in information systems research. MIS Q. 2011;35(3):553–572.

- Topol EJ. High-performance medicine: The convergence of human and artificial intelligence. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):44–56. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0300-7

- Raghupathi W, Raghupathi V. Big data analytics in healthcare: Promise and potential. Health Inf Sci Syst. 2014;2(1):3. doi:10.1186/2047-2501-2-3